Alaska to save memorial dedicated to black soldier workers

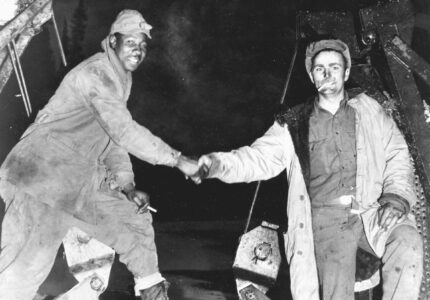

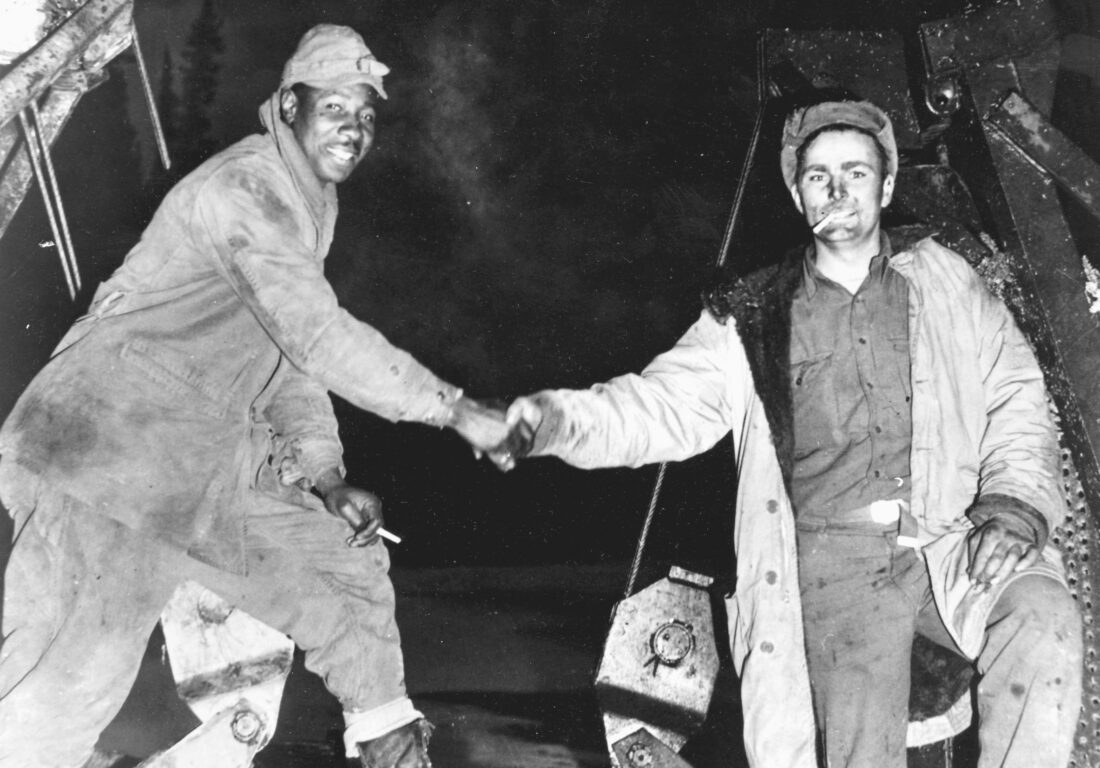

This Oct. 25, 1942, photo shows Cpl. Refines Slims, Jr., left, and Pvt. Alfred Jalufka shaking hands at the "Meeting of Bulldozers" for the Alcan Highway in the Yukon Territory in Beaver Creek, Alaska. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History via AP, File)

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Thousands of Black soldiers performed the backbreaking work of transforming rough-hewn wilderness in extreme weather swings during World War II to help build the first road link between Alaska and the Lower 48.

The work of the segregated Black soldiers is credited with bringing changes to military discrimination policies. The state of Alaska honored them by naming a bridge for them near the end point of the famed Alaska Highway.

Now, eight decades later, the aging bridge needs to be replaced. Instead of tearing it down, the state of Alaska intends to keep two of the bridge’s nine trestles in place as a refashioned memorial. The others will be given away.

Spans to be memorial

The state of Alaska will replace the 1,885-foot bridge that spans the Gerstle River near Delta Junction, the end point of the Alaska Highway about 100 miles south of Fairbanks.

Seven of the bridge’s trestles are being offered for free to states, local governments or private entities who will maintain them for their historical features and public use.

The two remaining spans from the old bridge, renamed the Black Veterans Memorial Bridge in 1993, will honor the 4,000 or so Black soldiers who built the first wooden bridge over the river while completing the Alaska Highway.

U.S. Army integration

The project to build a supply route between Alaska and Canada used 11,000 troops from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers divided by race, working under a backdrop of segregation and discrimination. Besides transforming the rugged terrain, the soldiers had to deal with mosquitoes, boggy land, permafrost and temperatures ranging from 90 degrees F to minus 70 F.

“Though conditions were harsh for all, they were nearly unbearable for black soldiers. From the Deep South, most of these soldiers had never encountered anything approaching the severe conditions of the far north. Moreover, since black troops were not typically permitted to use heavy machinery, they made do with picks, shovels and axes. In addition, they were prohibited from entering towns and were confined to wilderness assignments,” according to a historical account by the National Park Service.

It took Black soldiers working from the north just over eight months to meet up with white soldiers coming from the south to connect the 1,500-mile gravel road, then called the Alcan Highway, from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Delta Junction Oct. 25, 1942.

“In light of their impressive performance, many of the black soldiers who worked on the Alcan were subsequently decorated and sometimes deployed in combat. Indeed, the U.S. Army eventually became the first government agency to integrate in 1948, a move that is largely credited in part to the laudable work of the soldiers who built the Alcan,” the National Park Service says.

Japanese attacks

Alaska was still a territory, and officials long wanted such a road to the Lower 48. However, battles over routes and its necessity led to delays.

Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and Dutch Harbor in Alaska, along with the Japanese invasions of the Alaska islands Kiska and Attu signaled urgency for the road since the ocean shipping lanes to the West Coast could be vulnerable.

Black soldiers working near Delta Junction built a temporary bridge over the Gerstle River in 1942. Contractors finished the steel structure two years later.