No. 1 Indiana looks for storybook ‘Hoosiers’ ending Monday night

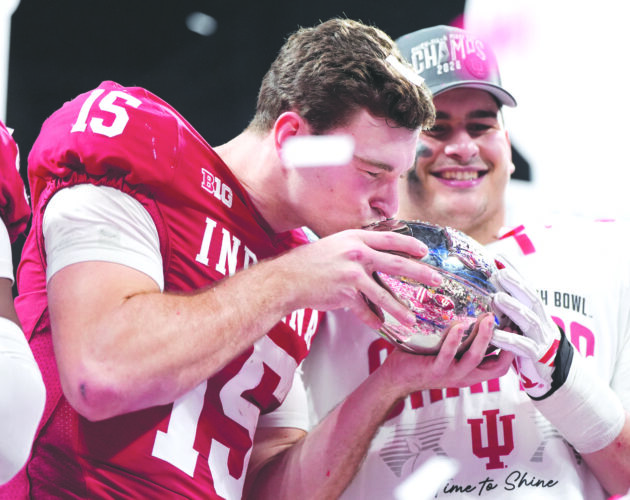

Indiana quarterback Fernando Mendoza, left, kisses the trophy after the Hoosiers won the Peach Bowl CFP semifinal against Oregon on Jan. 9 in Atlanta. (AP photo)

Long before Angelo Pizzo penned the scripts for two of America’s most iconic sports movies, he and his father would make the one-block walk from their home to Indiana’s football stadium.

The strolls home usually seemed to take a bit longer because even then, in 1955, losses were the norm. Eventually, the man who introduced the world to such motivational flicks as “Hoosiers” and “Rudy” accepted the reality Indiana’s program may be permanently stuck in mediocrity — or worse.

Pizzo found himself in good company in these parts.

Seventy-one years later, he — like so many other long-suffering Indiana fans — has a new perspective. Suddenly, the Bloomington native is bursting with excitement, enthusiasm, even a sense of disbelief as the Hoosiers have gone 26-2 over the past two seasons and he’s now heading to Miami to watch his beloved alma mater try to pull off a “Hoosiers”-like ending by beating the 10th-ranked Hurricanes on their home field for the program’s first national championship.

“One of my first memories, talk about being in my DNA, was we always lost,” Pizzo told The Associated Press this week. “That’s kind of like, except for a couple blips along the way — certainly the (1968) Rose Bowl team, I was in school there and the boys Jade Butcher, John Isenbarger, Harry Gonso were all good friends of mine — so that was a great adventure. I thought we’d turned the corner and then it went back down. It returned to what was normal and we went back to losing.”

Storybook turnaround

Curt Cignetti promised to change Indiana’s image from the moment he took the job five days after the end of the 2023 season. The no-nonsense 62-year-old coach neither minced words nor wasted them when asked at his first news conference why people should believe he’d end all this losing.

“I win. Google me,” he famously boasted that day.

It was a brash, bold statement from someone tasked with fixing a program that hadn’t won a bowl game since 1991, an outright conference title since 1945 and carried the banner of losingest major college team in the country.

Rather than tamp down the expectations, though, Cignetti doubled down at a basketball game.

“Purdue sucks, but so does Ohio State and Michigan,” Cignetti said to roaring cheers.

Pizzo and other fans were understandably skeptical.

For decades, they’d seen hopeful coaches come promising big turnarounds only to depart when they failed to achieve such lofty goals in front of half-filled stadiums.

How bad was it?

When coach John Pont had the Hoosiers fighting for Big Ten crowns in the 1960s, fans enjoyed chanting “Punt, John, Punt.” In 1976, then-coach Lee Corso called timeout in the second quarter to snap a photo of the scoreboard with Indiana leading Ohio State 7-6. They lost 47-7.

In the 1990s and 2000s, some tailgaters never made it inside the stadium, which prompted coaches to rally students to show up. And twice, Indiana took aerial photographs of sellout crowds clad in red — when the Buckeyes came to town.

On the field, it was equally abysmal.

In addition to the 713 all-time losses Cignetti inherited, the Hoosiers also had lost five of its previous six against dreaded rival Purdue and was 9-18 since 1997 against the Boilermakers. Plus, they had only one win over the Wolverines since 1988 and none over the Buckeyes since 1989 — the longest active skid against one team in the Football Bowl Subdivision.

Athletic director Scott Dolson had a different vision for the program, one Cignetti shared.

“I remember even during our first conversation, I said to him, ‘Curt, do you really believe you can win here?'” Dolson told the AP. “He just said, ‘Scott, if I have average resources, I’m 100% sure I will win here. There’s no question about it.'”

Invest in success

Perhaps the greatest impediment to success was the perception Indiana wasn’t fully invested in football. Salaries for head coaches consistently lagged near the bottom of the Big Ten and each new coach seemed to be fighting to get their assistants paid, too.

The change began when former athletic director Fred Glass started upgrading facilities. But when NIL money and the transfer portal changed the college football world, Indiana didn’t adapt quickly and the delay led, in part, to the firing of coach Tom Allen in 2023.

According to the Knight-Newhouse database, Indiana’s football budget has increased from $24 million in 2021 to more than $61 million last year.

Allen, who grew up in Indiana and whose father was a longtime high school coach in the state, landed at Penn State as defensive coordinator in 2024 and then took the same job at Clemson last season. Today, he’s impressed with the results — and the commitments.

“Just really, really happy for those guys and just really, really happy they’ve chosen to invest in football,” Allen said in December. “That’s something they know they needed to do. They had not done that in the past to the level necessary, and it’s been awesome to see them recognize that and invest and be able to be rewarded for that.”