A hard pill to swallow

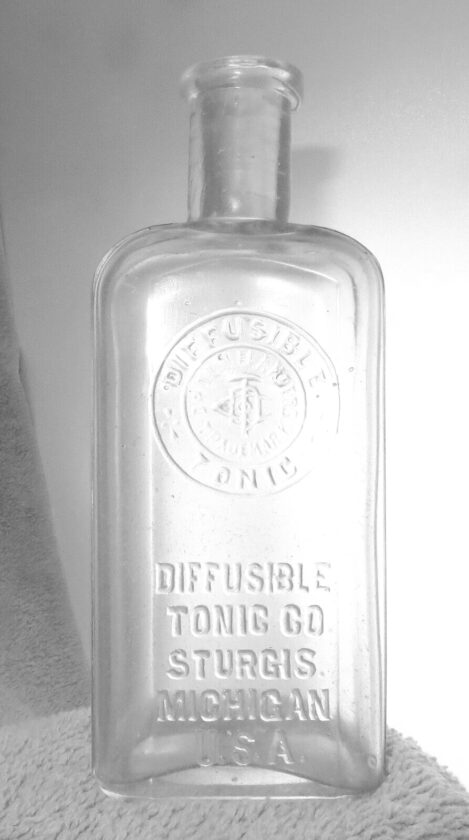

Pictured is a Diffusible Tonic Co. bottle. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

MARQUETTE — In contrast to today’s highly regulated healthcare industry, 19th century Michigan had few regulations regarding medical care. Any person, however uneducated, could set themselves up as a doctor, treat patients, sign death certificates, testify as an expert witness in murder trials and even recommend commitment of people to insane asylums.

The general populace had few mechanisms to distinguish a good physician from a quack snake oil salesman. But even the care administered by “good” physicians were often of questionable value.

Prior to and during the Civil War, “laudable pus” was once considered to be a sign of a healthy healing process, rather than the warning sign of an infected wound. Bloodletting (cutting into veins or arteries to remove blood) was a common treatment. Even famed local physician, Dr. Van Riper, in Champion is said to have favored a cough medicine recipe containing pine tar, cherry bark extract, alcohol, sugar, and laudanum (opium).

One of the most commonly prescribed medications was calomel, a mineral containing mercury chloride. Calomel was used as a purgative and anti-inflammatory treatment for various ailments including constipation, mumps, typhoid and yellow fever. Yet it also caused the destruction of jaw bones and teeth, mouth issues like excessive salivation and even neurological issues due to mercury poisoning.

While some medications were available commercially, physicians routinely measured, mixed and bottled the medications they prescribed and could compound their own pills. Ingredients were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle, then carefully measured out. The ingredients were mixed with a binding agent such as water or glucose syrup to make a pliable paste.

The paste would be rolled out, into either a thin cylinder (“pipe”) or a thick sheet, before being cut into small, uniform pieces. The cut pieces could be rolled by hand or a pill machine to make round or oblong pills. The newly formed pills would then go into an oven until they had dried and hardened. Some pills were coated in substances such as talc or gelatin, to make them easier to swallow.

One of the more notable “medicine men” to visit Marquette County was Dr. D. L. Flanders of Sturgis in the Lower Peninsula. He came to Negaunee during an 1889 typhoid epidemic. He was selling “Diffusible Tonic,” a remedy for fever which he alleged would “knock out every case of typhoid fever in the city, unless the fever has advanced to such a stage that nothing further can be done for the patient by human skill.”

Dr. Flanders claimed to have used the medicine to great success in treating cases of yellow fever in Florida and other locations. The newspaper and local doctors were somewhat skeptical of Dr. Flanders’ claims, but he offered both consultations and the medicine free of charge, depending entirely on future sales for compensation.

Despite their concerns The Mining Journal advised people to call on Dr. Flanders, “It costs nothing and there may be much gained by it.” “If it is as powerful as it is said, the danger from a typhoid fever epidemic is practically over.” Dr. Flanders remained in Negaunee for two weeks, “Treating a large number of cases with ‘signal success.'” His medication was also utilized by the local physicians and the nursing sisters of St. Joseph, who also reported success in treating patients.

A later examination of the tonic by the state board of health concluded that it contained quinine, which would have been helpful in treating malaria and possibly typhus as well, and goldenseal, which may have antibiotic properties. It may have had a marginal benefit for those taking it.

To learn more about the “golden age of quackery,” when medical science was floundering and anyone could legally put anything in a bottle and say that it would cure all ills of man or beast, join the Marquette Regional History Center for Here Comes the Wizard Oil Wagon: Senior Support Series at 1:30 p.m. Wednesday, Nov. 5.

Local history buff Bill Van Kosky will discuss the arrival of various traveling medicine shows which consisted of free musical performances and humorous skits, plus sales pitches for whatever medicine the self-proclaimed “doctor” was selling.

This daytime SSS program also includes an antique medical equipment display by Chip Truscon, door prizes and complimentary Dead River Coffee. All ages are welcome. This is a free program. For more information, visit marquettehistory.org or call 906-226-3571