Police Chief Timothy T. Hurley III profiled

Marquette Police Chief Timothy T. Hurley III. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

- Marquette Police Chief Timothy T. Hurley III. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

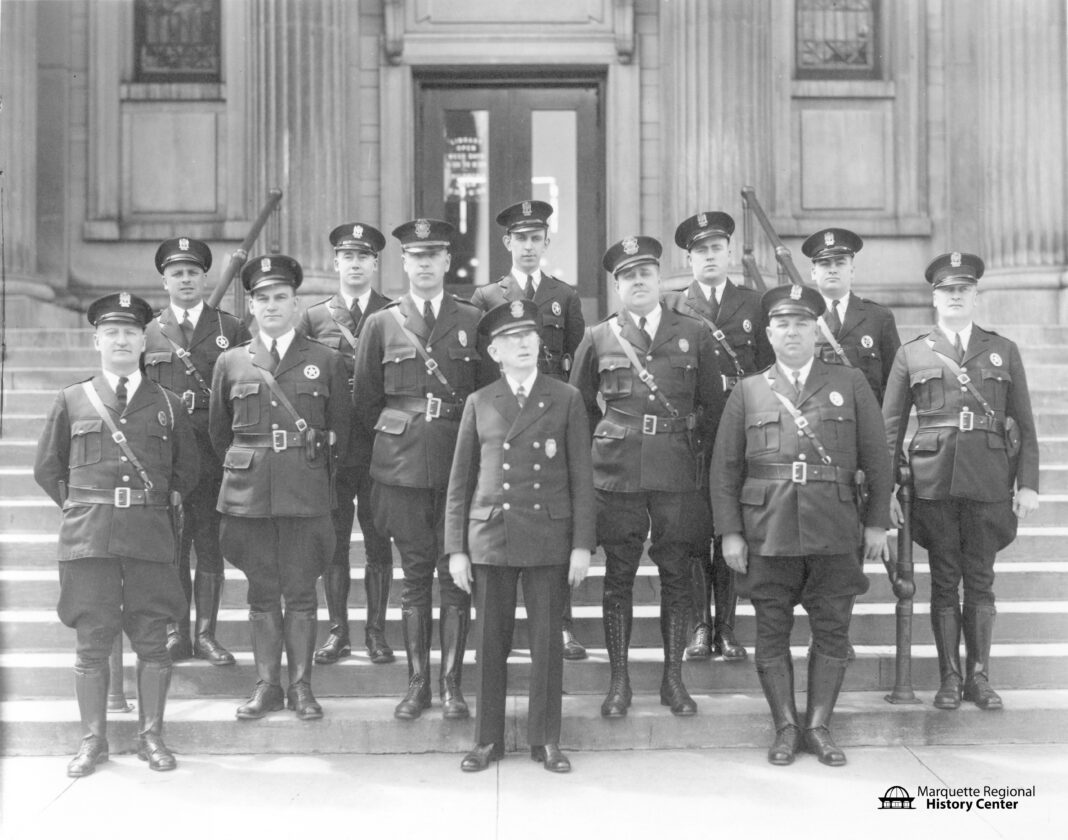

- The entire Marquette Police Department, with Chief Timothy T. Hurley III out front, is pictured. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

On November 26, 1890, he married Delia Duyore at St. Peter’s Cathedral in Marquette. The couple went on to welcome six children: Walter, Timothy (George), Howard, Arthur, Delia, and Helen.

Timothy’s first law enforcement job was as a deputy United States Marshall for the western district of Michigan. In 1925, he transferred to the Federal Prohibition Service under the United States Internal Revenue Service, enforcing the National Prohibition Act of 1919, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages.

In January 1929, Hurley was named police chief. One of the first police orders that he signed prohibited sledding (called “coasting” in newspaper reports) down Genesee Street due to the high volume of traffic and apparent danger from the intersection of Division and Genesee Streets.

Other changes that Chief Hurley implemented in the police department included improving the officers’ pistol marksmanship with weekly target practice. He assigned an officer in the police station overnight, providing 24/7 phone access. He marked the first “stalls” on east Washington Street to ease parking congestion. He eliminated U-turns at intersections in the business district. He implemented the overnight winter on-street parking ban to ease plowing

The entire Marquette Police Department, with Chief Timothy T. Hurley III out front, is pictured. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

The chief had a few sayings that he often repeated. One was: “Big oaks from little acorns grow,” stemming from the idea that children are not born to be criminals, but circumstances like having no parental guidance or bad environment can make them that way. Chief Hurley realized that while he couldn’t parent everyone’s son or daughter, he also couldn’t chase them all over town to arrest them to solve the problem. He instead tried to befriend the children and set them on the right path.

In one example, there was a highly publicized wrestling match at the Palestra between Gus Sonnenberg and Stanley Stasiak. Many local boys wanted to see the event, but they couldn’t pay. The chief realized that the boys were ready to do most anything to gain entry, including breaking windows and doors. Seeing an opportunity to further public relations, he negotiated with the promoters to allow the boys into the match free of charge.

Another time, while Chief Hurley was patrolling the streets, he saw a young lad of six or seven years of age “hitching” a ride on a local streetcar by attaching himself to the rear of the vehicle and then jumping off when it stopped. The child was nearly run over by a vehicle driving behind the streetcar. Chief Hurley asked the boy his name and the boy said he “couldn’t remember.” The chief understood that by waiting the boy out and talking to him calmly, he would soon get his answer. Eventually the boy did “remember” his name, and he was returned to his parents.

Always safety conscious, he instructed local schools to start ensuring the safety of children walking to and from school. Eleven public schools organized safety patrols with 46 junior patrol officers, each furnished with an armband and a Sam Browne belt. Reports indicated the program was very successful and cut down on the number of accidents in which children were involved.

The chief believed that busy bodies would have no time for mischief, so in the early 1930s he set out to give young people opportunities to “let off steam” and started to develop the idea for a playground in South Marquette. The location chosen was Genesee and Adams Streets. The newspapers reported in November that the field would be ready for use “before the snow flies.” Since it was opening close to the winter season, it was decided that the first use of the space would be as an ice rink. It had modern conveniences, and lighting was installed by the light and power company. This lighting consisted of 12 poles with 300-watt lightbulbs to illuminate the area. The field was intended to rival the Longyear Field in North Marquette.

Chief Hurley endorsed the Boy Scouts as a worthwhile organization, saying that an investment in the Scouts prevented a lifetime of criminal activity. He stated that 9 out of 10 delinquents began their careers with petty offenses, but that boys who became involved in the Boy Scouts found better opportunities for spending their leisure time. In 1932, local Boy Scouts volunteered 1,827 hours of civic service to the community.

In 1934, Chief Hurley lost the use of his middle finger while removing an old weapon from a gun cabinet. He was holding the barrel of the gun in his left hand when he accidentally pulled the trigger.

Chief Hurley resigned in May 1937 due to his advancing age. He died 12 years later in November 1949 at the age of 83.