Mapping Michigan: Surveying changes over the generations

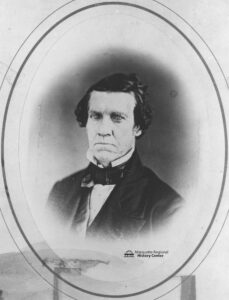

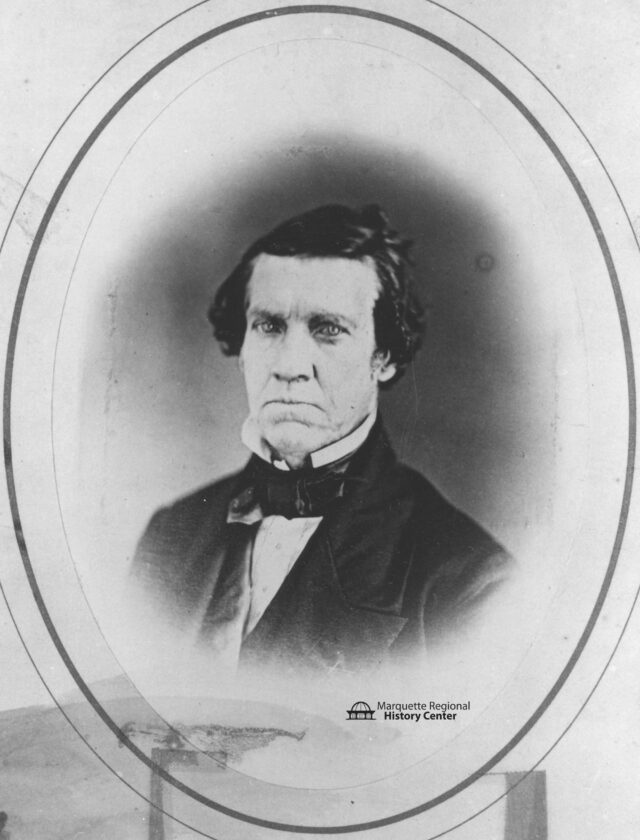

This is a portrait of William Austin Burt (1792-1858) (Photo courtesy Marquette Regional History Center)

- This is a portrait of William Austin Burt (1792-1858) (Photo courtesy Marquette Regional History Center)

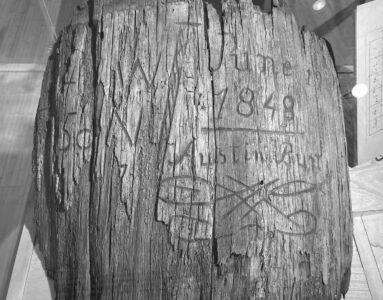

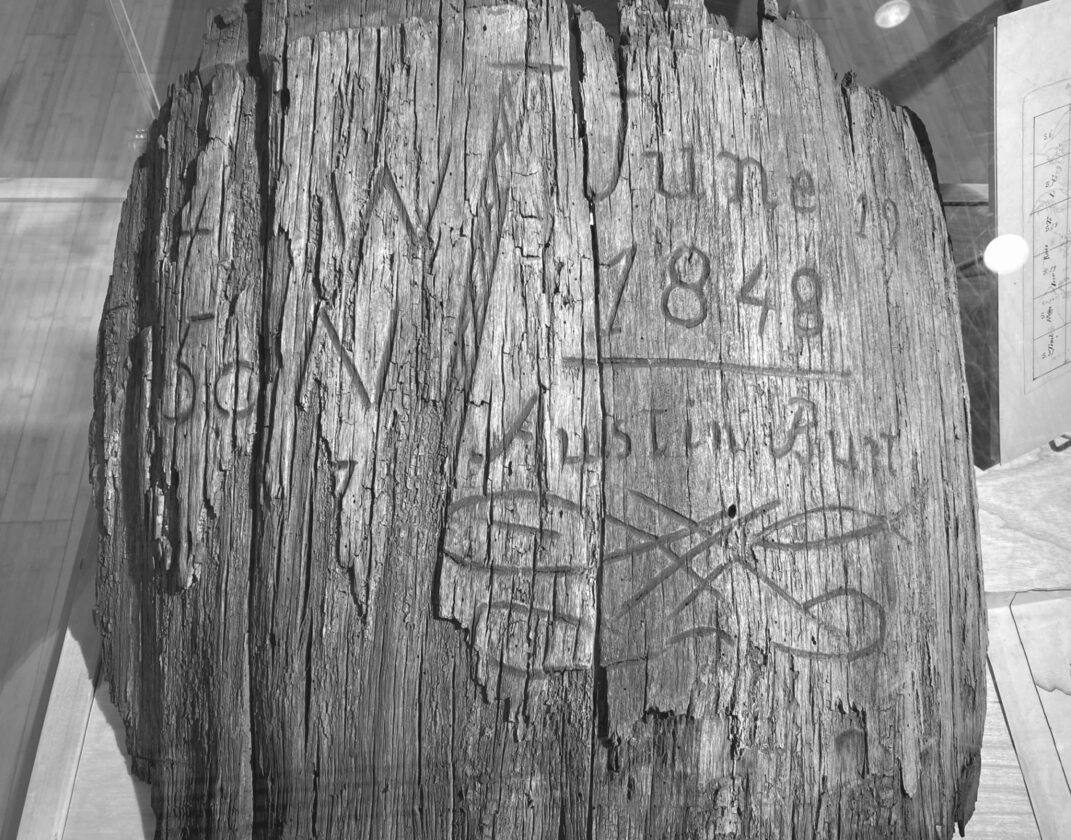

- This bearing tree was carved by William A. Burt on June 19, 1848. It was originally located at 4-W, 50-N in Ontonagon County and is currently on display in the Marquette Regional History Center’s special exhibit, “Mad About Maps.” (Photo courtesy Marquette Regional History Center)

Starting with rudimentary tools, including knotted ropes and plumb bobs, the ancient Egyptians would resurvey land boundaries following the Nile River’s annual floods.

Establishing property lines was necessary for taxations, land management and resolving disputes.

By the time of the Roman Empire, the need to create land registers for newly conquered lands led to surveying being recognized as a profession. Terminalia, a festival in honor of Terminus, the Roman god of landmarks, involved dancing and sacrifices at boundaries.

Terminalia is believed to have evolved into the practice of “beating the bounds” during the Middle Ages in Europe. Either annually or every seven years, a group of local residents would walk the boundaries of their community, using folk memory to maintain them.

This bearing tree was carved by William A. Burt on June 19, 1848. It was originally located at 4-W, 50-N in Ontonagon County and is currently on display in the Marquette Regional History Center’s special exhibit, “Mad About Maps.” (Photo courtesy Marquette Regional History Center)

Led by the priest with prayers for the community’s safety, they beat local landmarks with green boughs of birch or willow. Young boys would be specifically included with the intention that witnesses to the boundaries should survive as long as possible.

In North America, pre-contact tribal boundaries varied greatly, reflecting a different economic system, diverse adaptations to different environments and cultural practices. These boundaries were not always clearly defined or fixed, and were often based on factors like kinship, resource utilization and seasonal movements, rather than taxation. Mapping these boundaries is complex, as many were based on oral traditions and shifted over time.

After European colonists began creating permanent settlements, they also began imposing their own boundaries on the land. The original 13 colonies had been surveyed based on the British system which describes lines based on local markers.

Following the Revolutionary War, the U.S. General Land Office was formed in 1812 to survey public lands. The newly created U.S. government, which needed funds, wanted to distribute the land to war veterans as a reward and to sell land to raise funds. The Public Land Survey divided the territory into a grid system of townships, sections and quarter sections to promote ownership and development.

Surveyors were contracted by the federal government and had to include the variations of every line they ran; the name and diameter of all bearing trees; the surface — level, rolling, broken, hilly; the quality of soil; the type of timber and undergrowth; the rivers and their courses; all springs; all ponds, including the banks, water depth and quality; waterfalls and mill sites; all towns, camps, furnaces and constructions; all minerals and ores; and roads and trails.

Traditionally, surveyors used a special metal chain for measuring distances along with a spring and thermometer. Tension and temperature of the metal all affect the measurement. A rod was used in finding elevation. A survey party might consist of a surveyor, rodman and two chainmen.

Surveying Michigan Territory began in 1815 with the establishment of a base line and prime meridian. When the territory was first surveyed, a wooden post was used to mark each section and quarter section.

Around each post were up to four bearing trees (also known as witness trees). They were each blazed or marked. The trees’ species, diameter, and location — the distance and direction from the post — were all recorded in a log book.

Later survey markers or monuments, often made of metal, were placed at key survey points on the Earth’s surface.

Most of the Lower Peninsula and eastern Upper Peninsula were completed by 1840. However, much of it was found to be inaccurate and even fabricated. One story circulated that the surveyors simply sat around a tavern and made up the terrain in northern Lower Michigan.

One of the surveyors defended himself, claiming no one was harmed and the land was worthless: “Was ever any individual or even was the United States injured? Was the country worth a cent? No, the land will not be sold in 10 centuries,” which was quoted in “Getting Southern Michigan into Line,” Michigan History Magazine J/F 2003, p. 26.

In the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe, the Ojibwe ceded extensive tracts of land that are now the western half of the U.P. and the northern part of Wisconsin. William Austin Burt (1792-1858) was a U.S. government deputy surveyor whose work took him into wilderness areas where he and others ran the lines that divided the two peninsulas of Michigan into a checkerboard of townships and sections as prescribed by the Ordinance of 1785.

On Sept. 19, 1844, near Teal Lake in what is now Marquette County, Burt and his men found their compasses acting in a most irregular fashion. A search for the cause revealed numerous specimens of magnetic ore — the Marquette Iron Range.

Burt went on to invent the solar compass, which is not affected by the magnetic charge of iron ore and became the standard tool. The survey of Michigan was finally completed in 1851.

The U.S. Geological Survey has been the country’s primary civilian mapping agency since 1879. In 2009, the USGS transitioned from hand scribed topographic maps to U.S. Topos, which are computer-generated on a regular schedule using national databases.

Electronic measuring devices, the Global Positioning System, and Light Detection and Ranging (lidar) are used in surveying today. Lidar is a remote sensing method that uses lasers to create three-dimensional models. Aerial and satellite photography is also used in making maps today.

(REST OF THIS IN ITALICS)

To view maps of the Great Lakes and Marquette County, see how mapmakers have sometimes misled their viewers and how our landscape and surroundings have changed, visit the Marquette Regional History Center’s Special Exhibit: Mad about Maps on display through January 31, 2026.

For younger map enthusiasts ages 8-12, our Hands On! Art and History Day Camp in partnership with the Liberty Children’s Art Project will explore art media and projects themed to the map exhibit. It will be held from 10 a.m. to noon on Monday through Friday, Aug. 18-22. The location is the Marquette Regional History Center building, 145 W. Spring St. in Marquette, except on Tuesday, which will be held at Park Cemetery off of North Seventh Street. Cost is $55 for the week ($50 for museum members) with a sibling discount available. Preregister at the museum or call us at 226-3571, as space is limited.