Keweenaw Military Wagon Road recalled

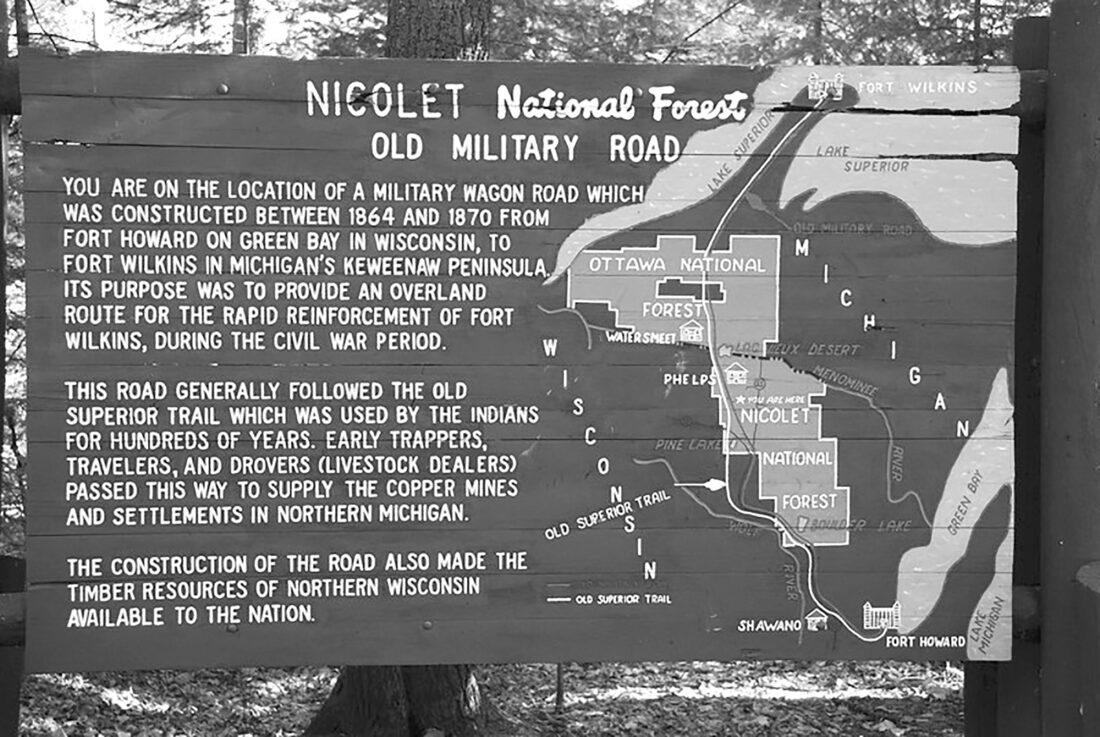

This historical marker shows the route of one military road in the Upper Peninsula and northern Wisconsin. (Courtesy photo)

KEWEENAW — The United States military constructed a network of wagon roads or improved existing roads during the 19th century. These roads facilitated the movement of troops, supplies and settlers across the country.

There were over a dozen military roads in Michigan. Among the most prominent were Detroit to Chicago, built in 1825 it is now U.S. 12; Detroit to Port Huron, built in 1829 and Saginaw to Mackinaw City, built in 1864, modern I-94 and I-75 approximately follow these routes. In the Upper Peninsula, the Keweenaw Military Wagon Road ran from Green Bay, Wisconsin to Copper Harbor at the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula.

Talk of a military road to the Keweenaw began in 1843 with the copper rush, as miners, explorers, and scientists flocked to the area. They were spurred by Douglass Houghton’s fourth annual report from the Michigan Geological Survey, which noted rich copper deposits in the region.

Fort Wilkins, a U.S. Army base, was built near Copper Harbor in 1844 in anticipation of conflicts between the local Native Americans and the encroaching miners. When these conflicts failed to materialize, the fort was closed in 1846 and the soldiers were sent south to fight in the Mexican American War. Without a fort in the region, the military had little reason to build the proposed wagon road.

In 1848 the Michigan State Legislature sent a joint resolution to Washington, D.C. asking for, “…an appropriation from the general government for the construction of a military road from some eligible point on Green Bay, Lake Michigan to Keewawenon [sic] Bay, Lake Superior.” Despite this request, Congress took no action regarding the construction of the road.

As the region continued to develop and the federal government still hadn’t built the road, Houghton County acted. In 1855-1856, the county authorized the construction of a road from “Copper Harbor by way of Agate Harbor, Eagle Harbor, Eagle River to Portage Lake.” If this route sounds familiar to you, it is now M-26.

This action was soon followed by the State of Michigan authorizing the “Mineral Range State Road” from “Point Keweenaw to Ontonagon” in 1857, as well as the “Ontonagon and State Line Road” which connected Ontonagon to the Wisconsin state line in 1861.

The beginning of the Civil War changed the situation significantly. Three quarters of the Union’s copper came from the Keweenaw and ensuring its safe transport was essential. In March 1863, Congress authorized the construction of, “… a military road from Fort Howard, Green Bay, Wisconsin via Portage Lake to Fort Wilkins, Michigan.”

At 220 miles long, the proposed road was to be, “… no less than 40 feet wide with a travel surface not less than 16 feet wide with such graduation and bridges to permit its regular use as a wagon road in all seasons of the year as the states may prescribe.” The instructions also noted that when crossing swamps, “… the roadway shall be covered with a covering of timber.”

The project was to be paid for by land grants made to both Michigan and Wisconsin, with the legislation specifying, “… every alternate section of public land, designated by even numbers, for three sections in width, on each side of said road.” The land grants gave the two states the ability to sell or develop the land next to the new road. The Michigan legislature accepted the land grant in February 1864.

The state then appointed three men to lay out the most direct route for the road- John Senter of Keweenaw County, John H. Forster of Houghton County, and William E. Dickinson of Ontonagon County. One the changes the three made to the proposed route was moving the road 15 miles to the west to incorporate the preexisting Ontonagon and State Line Road into the Keweenaw Military Road.

Much of the construction work was done by the U.S. Military Road Company. The company’s articles of incorporation state that its purpose was to build the road, but then despite its name, added it was also interested in, “… establishing and running a line of stages; mining for gold, silver, copper, iron and other metals; establishing smelting works; quarry marble, slate, and other stones; … building grist and saw mills, etc.”

With this lack of focus, it doesn’t seem all that surprising that the company missed the 5-year federal deadline and repeated renewals for finishing the project. The company also contended with labor shortages and deaths among the managers.

The Wisconsin section of the road was completed in June 1870, followed by the Keweenaw section in August 1871 and finally the entire Michigan section was completed in 1873. By the time the road was completed, it had little strategic military value. Fort Howard in Green Bay had been decommissioned in 1853, and Fort Wilkins had been briefly re-garrisoned with soldiers serving out their Reconstruction enlistments in 1867 before permanently closing in August 1870.

The real value from the Keweenaw Military Road came from the economic and civil development spurred by the transportation corridor linking the Keweenaw to the outside world. The greatest impact was felt in southern Houghton, Ontonagon and Gogebic counties.

Additionally, the land grants awarded for building the military road covered 221,000 acres (345 square miles). Ultimately much of this land went on to become the eastern side of the Ottawa National Forest created in 1931.