From cigars to snow fences; Manufacturing at Marquette Branch Prison

The Vocational Carpenter's Shop at the Marquette Branch Prison, June 23, 1939, is shown. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

MARQUETTE — Earlier this year, publicity about prison inmates fighting the Los Angeles fires raised the question of jobs held by prisoners in Michigan, and specifically in Marquette.

Michigan’s first state prison opened in Jackson in 1839. The location was chosen after extensive lobbying by local businessmen looking for a source of cheap labor. Inmates were not only escorted to local factories to work, but one manufacturer of wagon wheels even built a factory on the prison grounds. Prisoners also worked in factories, eventually making everything from tombstones to auto parts.

The model was financially successful from the business perspective, quickly making Jackon the largest railroad stop between Chicago and Detroit. It also had the advantage from the taxpayers’ point of view of not only underwriting the cost of running the prison, but often also producing a net profit. Not surprisingly, the prisoners were less fortunate, earning only pennies a day for their difficult and frequently dangerous labor.

When Marquette Branch Prison opened in 1889, the earliest inmates included three prisoners from Jackson who were skilled carpenters and masons who were then assigned to lead the crews building the prison walls. Early female inmates worked in the kitchen and laundry. The women also worked in one of the first industries at the Marquette prison–a hosiery mill established in 1890. A brush and broom factory opened soon afterwards, and the prison farm also helped provide some income.

By 1892 the warden reported that the prison was producing enough profit that it did not need support from the state for at least that month. In 1897 the prison got a contract to produce cigars for a Chicago firm. The prison was to be paid $1 for every 1000 cigars manufactured, and the prison tried to reassure local businesses by saying they would all be shipped out of state.

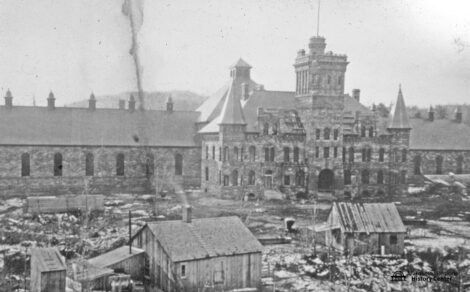

Pictured is construction of the State Branch Prison at Marquette, circa 1885-1887. (Photo countesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

But in both Jackson and Marquette–and indeed throughout the nation–prison industries were increasingly viewed as undercutting private enterprise. The cigar makers union, for example, strongly objected to the Marquette cigar factory. The Lamb Knit factory in downstate Colon objected that the prison hosiery plant was using the same machines (machines, in fact, that had been invented by Isaac Lamb) to produce the same items and selling them at half the cost.

The contract labor continued, however. Though the cigar factory b

- The Vocational Carpenter’s Shop at the Marquette Branch Prison, June 23, 1939, is shown. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

- Pictured is construction of the State Branch Prison at Marquette, circa 1885-1887. (Photo countesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

News of the abuses suffered by prisoners reached the Michigan legislature, where a bill was introduced to ban flogging. The head of the company buying the overalls vigorously opposed the bill, but his protests backfired, and in that same year the Board of Prison Industries recommended doing away with all contract labor. Instead, “Prison labor should be entirely utilized by the state in industries that will yield a more substantial profit when they are placed on sale in fair competition with free labor.”

This did not mean the end of prisons using inmates to generate profits. Instead, prisons opened their own industries. In Marquette, the prison simply purchased the equipment used by inmates working for a local box factory and rebuilt the factory on the prison grounds. The prison also continued to make overalls and gloves and operated a sawmill.

In the mid-1920s, the Cloverland Retail Lumberman’s Club began complaining that the Marquette prison sawmill was selling lumber to the public. Although the Marquette warden originally denied this, it turned out the prison was actually running ads for its lumber. The outside sales were shut down.

By the early 1930s federal and state laws effectively banned the sale of prison-made goods to the public. From that point forward, prison factories were limited to making items for sale to state agencies and, eventually, mostly for use within the prison system itself. Marquette, for example, had a factory to make bricks and cement blocks to be used for construction at the prison. For a time, a shoe factory made shoes for prisoners.

Marquette also benefited from having long-term inmates become skilled workers. It was for this reason that in 1940 a clothing factory was moved to Marquette from the prison at Ionia. During World War II the clothing factory worked double shifts of 100 men per shift turning out uniforms for the state militia and fatigues for the army and navy.

After the war the factory continued, making overalls, coats, jackets, jeans, slippers, and blankets for prisons and other state institutions, often using cloth that had been woven in a factory at Jackson prison. A brush factory also turned out 7000 brushes in 46 different styles every month. This factory, too, had been moved from Ionia, in this case, to be closer to the source of the hardwood used for the bodies of the brushes.

Two other notable industries in Marquette harkened back to the earliest days of prison industries here. The first was the sawmill, which not only produced wood used for the brooms and brushes but also made almost all of the snow fences used by the Michigan Department of Transportation. The other was a tobacco factory, which for decades used as much as 100,000 pounds of tobacco each year to produce chewing and pipe tobacco and the especially popular “rollings” which packaged loose tobacco with rolling papers so inmates could roll their own cigarettes.

Today, fewer than 2% of all inmates in Michigan work in prison industries and there are no longer any factories at Marquette Branch Prison. But one industry has remained since Michigan pioneered it in 1910. Each year inmates at the Gus Hall Correctional Facility near Adrian make more than 1.5 million license plates.

Credit to Ike Woods’ “100 Years at Hard Labor: Centennial Edition” for much of the information in this article.