Polio, Marquette, and Kathleen Shingler Weston

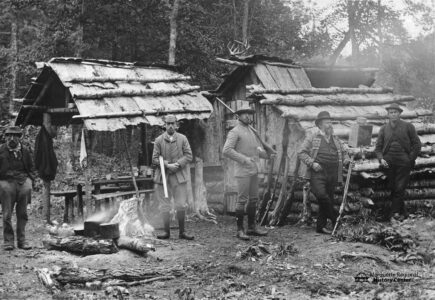

Max Reynolds and the homemade iron lung.

MARQUETTE — In the early 20th century, poliomyelitis, or polio, struck fear in parents around the world. The viral infection affects the central nervous system, and the victims of the disease are primarily children. While many cases result in a mild illness, a small number of serious cases can lead to muscle paralysis and cause lifelong disabilities or even death.

A polio outbreak began in 1938 in the Upper Peninsula and by the summer of 1940 an epidemic was underway. Then, beginning in July 1940, the U.P. experienced a polio outbreak of “unprecedented severity.” 320 cases of polio were confirmed. Although only nine patients were residents of the city of Marquette, 148 other cases from around the U.P. were transferred to Marquette, mainly St. Luke’s Hospital, for care. The effects of this outbreak were unusually severe, with the number of respiratory cases estimated to be near 10%. Thirty-three patients had respiratory complications, and 13 required respirators or iron lungs.

The reason patients were sent to Marquette and St. Luke’s was the iron lung. An iron lung is a negative pressure ventilator. The person using the iron lung is placed into the air-tight chamber from the neck down. Pumps that control airflow periodically decrease and increase the air pressure within the chamber, and particularly, on the chest. When the pressure is below that within the lungs, the lungs expand and atmospheric pressure pushes air from outside the chamber via the airways to keep the lungs filled; when the pressure goes above that within the lungs, the reverse occurs, and air is expelled. In this manner, the iron lung mimics the physiological action of breathing: by periodically altering intrathoracic pressure, it causes air to flow in and out of the lungs.

Early in the epidemic St. Luke’s was equipped with a single iron lung. By the end of August 1940, hospital staff knew that one wasn’t going to be enough. Growing concerned about the condition of two hospitalized children, the hospital called local businessman, Max Reynolds, to see if he could improvise a way to place two children in the one iron lung. It was decided that it wasn’t feasible to retrofit the ventilator while it was occupied.

But working with hospital engineer Lowell Reynolds [no relation], who provided instructions from a pediatric magazine, and several other men, including engineers, machinists, carpenters, ship-joiners, painters, sailmakers and errand boys, they set up shop in Max Reynold’s boathouse (now the Lake Superior Theatre) and got to work building a new iron lung. As they worked, they received calls from the hospital telling them to hurry because the patients were deteriorating and manual artificial respiration had begun.

Kathleen Shingler Weston

In just under four hours, they managed to construct a double unit, which could hold two children, out of spare parts and scrap materials. By the time they finished, one of the children had died but a third child was already developing respiratory symptoms. The first homemade unit was operated manually, with nurses and other volunteers opening and closing a valve every few seconds around the clock. Two days later, a record player was added to motorize the valve, turning it into an automatic unit.

Nine of these home-made iron lungs were made using these elements, two of which were double units. In December 1940 it was reported that Marquette had the largest grouping of respirators ever accumulated in the United States (although that record did not last long). The iron lungs were made out of salvaged materials including iron barrels and wooden crates. One of these crate lungs is on display in the main exhibit gallery at the Marquette Regional History Center

- Max Reynolds and the homemade iron lung.

- Kathleen Shingler Weston

Then following one of the largest clinical trials in history, on April 12, 1955, an announcement came from Ann Arbor, Michigan that Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine was both safe and effective. The announcement was compared to the end of World War II, signaling victory in the battle against the microscopic enemy.

Kathleen Shingler Weston, a UP native hailing from Kenton, a small community in Houghton County, worked on the Salk vaccine project for three years. Weston attended Kenton High School. At the time the combined elementary and high school had only 15 students and Kathleen was one of two graduates in her class. She next moved to the “big city” of Marquette, attending Northern State Teachers College (now Northern Michigan University) and graduating with a degree in biology in 1929. She continued her education, pursuing a master’s degree in anatomy and genetics at the University of Michigan in 1934 and her MD from Temple University Medical School in 1951.

Unlike other vaccine development of the time, which used live or weakened viruses, Jonas Salk and his team pursued a vaccine based on killed poliovirus. This innovative approach was safer and simpler to produce. Due to her experience with microscopes and the nervous system, Weston was hired by the pharmaceutical giant Parke-Davis and Company, one of six companies producing the Salk polio vaccine for children. Kathleen directed the infectious control tests of the vaccine to ensure no live virus was present. She considered her work on the vaccine to be her top scientific achievement.

To learn more about Kathleen S. Weston and other notable individuals in the community, join the MRHC for our annual Historic Bus Tours. Whether you live here or are visiting, you will be entertained by historic reenactors bringing to light the stories of buildings, people, and sites along the route while you relax in a comfortable air-conditioned Checker bus. We will feature the Marquette lakefront, downtown, historic homes, Park Cemetery, and sites north at the university. It is here on NMU’s campus that you may enjoy hearing from a reenactor playing Kathleen S. Weston, taking you back to 1929. The 90-minute tour departs from and returns to the MRHC.

Tickets are on sale now for $25 each and are available at marquettehistory.org/bus-tour-tickets or visit the museum store. Tuesday at 1 p.m. tours are on July 15, July 22, July 29, and August 5, while Wednesday at 6:00 pm tours are on July 16, July 23, Aug. 6, and Aug. 13. The MRHC would like to thank Checker Bus for their support with these tours.