Unincorporated community of Greenwood, part 1

A Marquette County plat map from circa 1916, shows lands owned by the Junak Family (also misspelled Jurah) in Sections 21, 28, and 29. (Image courtesy of the Marquette Regional History Center)

ISHPEMING — West of West Ishpeming lies the small unincorporated community of Greenwood and the Greenwood Reservoir, located in Ely Township. The blue waters of the basin and the surrounding forests conceal the area’s mining and farming history.

In 1865 the Marquette & Ontonagon Railroad Company (M&O), built a blast furnace to process iron ore about 12 miles west of Negaunee, along the railroad’s tracks between Marquette and Michigamme. The furnace was placed into blast that June.

Wages in Greenwood were good: furnace men made $2/day, laborers $1.50-1.75/day and wood choppers were paid $0.75-$1/cord of wood. Soon a community grew up around the furnace and railroad tracks. Platted in 1865, the village came to include 50 frame houses for the workers and their families.

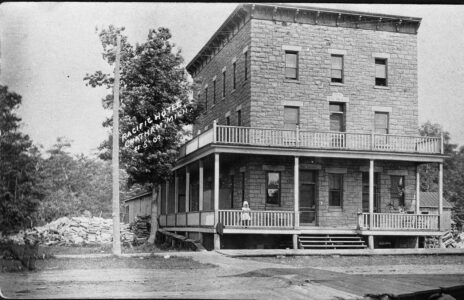

By 1867, the settlement boasted its own post office, a sawmill and a general store. The following year, the newly formed Michigan Iron Company purchased the Greenwood furnace and 8,000 acres of surrounding timberlands from the M&O.

Greenwood Furnace proved very productive for the Michigan Iron Company. 4,500 tons of pig iron were produced in 1871, consuming 125 bushels of charcoal for each ton of iron! By 1874 the furnace was making record monthly outputs, producing a total of 5,438 tons of iron that year.

Unfortunately, this success also contained the seeds of the community’s downfall. By 1873, the forests surrounding Greenwood had been leveled and the wood hauling roads from the new timber lands were terrible at best. The lack of wood for producing charcoal, the Financial Panic of 1873 and the subsequent depression of 1874-1879 led to the company filing for bankruptcy in January 1875.

The furnace was blown out and shut down in April 1875. By October that year, the post office had closed. Greenwood remained a station on the railroad until 1893, but the village quickly vanished.

It was just a few years later, around 1896, that Czechoslovakian immigrants, George Junak and his bride, Susan Besak, purchased 80 acres of rocky, hilly land beside the Escanaba River to establish their farm. The couple built a five-room farmhouse, constructed by hand from rough-hewn cedar logs and sealed with whitewash to guard against the cold winters.

George and Susan welcomed ten children while expanding the farm with buildings for horses, pigs, cows and chickens. Daughter Rose later remembered “Dad and the boys worked with grub hoes and brush hooks. It was slow and tedious clearing the pastures, grain fields, and garden plot. Dad complained that the rocks must have grown in the night, because there were so many…Each shingle for the roof was cut from cedar, shaped and then nailed in place.”

Tragedy struck when Susan died of tuberculosis in 1917, age 38. She left behind eight surviving children, ranging from George Jr., 18 to Helen, just three. The oldest daughters, Rose and Mary, took over the cooking and cleaning at home. The older boys began logging in the surrounding woods, using the profits to purchase additional land, eventually owning more than 1,000 acres.

When George Sr. died from cancer in 1935, the boys kept the logging operations going, while Rose, Helen and Margaret managed the farm with the assistance of hired hands. After their last caretaker died, the sisters moved closer to Ishpeming. The farmhouse remained a favorite retreat and hunting camp for several generations of Junak descendants, with weekly potluck dinners. By the 1970s, there were more than 100 direct descendants living within 10 miles of the original homestead.

A representative of Cleveland Cliffs Iron Co. approached the family in 1969 asking to purchase the farm and the adjoining property. The Tilden Project to mine and concentrate low-grade iron ore required 38 tons of water for every ton of ore produced and the company wanted to create a reservoir on the East Branch of the Escanaba River. After considering Michigan’s condemnation law, which enabled companies to obtain private property for industrial uses, the family decided to sell the property.

During public hearings regarding permitting for the project many environmental groups opposed the project, but in exchange for the Michigan United Conservation Clubs’ endorsement, CCI agreed to use part of the reservoir area for environmental education and conservation.

Beginning in Spring 1972, construction workers moved in with bulldozers, demolishing the farm buildings. For years the brothers had selectively cut the timbered portions, leaving a seed stock of young spruce and pine for future generations. CCI intended to harvest the timber but were prevented by the project’s schedule. Instead, the remaining trees were bulldozed into gigantic piles. The trees and remains of the demolished buildings were burned.

The dam was completed in Fall 1972 and in Spring 1973 the waters of the Escanaba River began backing up and covering the farmstead. By midsummer, the land was under 20-30 feet of water, forming a lake with 26 miles of shoreline. The Greenwood Reservoir was dedicated in August 1974, and the Tilden Mine produced its first ore concentrate in October.

As required by the deal with MUCC, the Greenwood Nature Center was founded on land leased from CCI with support from CCI and NMU in 1976. Three years later, a building was moved to the site. The center hosted around 2,000 people a year for school programs, teacher workshops, and public nature education programs, along with access to nature and cross-country ski trails.

Join the Marquette Regional History Center for a presentation by David Kronk, former director of the Northern Michigan University Greenwood Nature Center on Wednesday, May 28, at 6:30 p.m. at the MRHC and learn about the history of, and people behind, this community resource. $5 suggested donation. For more information, visit marquettehistory.org or call 906-226-3571.