Addiction’s cost

Community panel addresses painkiller abuse

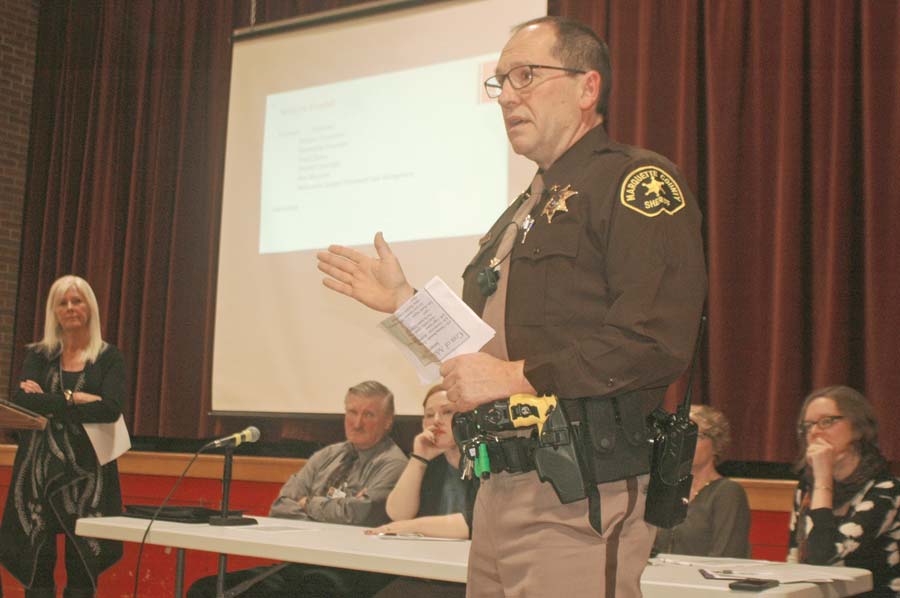

Marquette County Sheriff Greg Zyburt talks about substance abuse at a recent community panel entitled “The Cost of Addiction.” The event took place at Marquette Alternative High School at Vandenboom. (Journal photo by Christie Bleck)

- Marquette County Sheriff Greg Zyburt talks about substance abuse at a recent community panel entitled “The Cost of Addiction.” The event took place at Marquette Alternative High School at Vandenboom. (Journal photo by Christie Bleck)

- Members of the panel audience raise their hands to show they’ve been impacted by substance abuse in one way or another. (Journal photo by Christie Bleck)

- Morphine is a pain medication that is addictive if used improperly. (Journal file photo)

“If that doesn’t sound the drum that there’s an epidemic out there, it’s something that we certainly need to pay attention to,” said Greg Toutant, chief executive officer of Great Lakes Recovery Centers Inc., at a Wednesday community panel entitled “The Cost of Addiction.”

Members of the legal, health and education communities met in front of a packed gymnasium at Marquette Alternative High School at Vandenboom.

Addressed at the event was what opioid/opiate addiction does to the community.

According to opium.com, opiods and opiates, which come from from the opium poppy plant, are known for their ability to relieve pain. Opioids are synthetic drugs that produce opiate-like effects.

Morphine is a pain medication that is addictive if used improperly. (Journal file photo)

However, medically speaking, “opioid” refers to any substance that binds to the body’s opioid receptor sites.

Technically speaking, not all opioids are opiates, but all opiates are opioids; heroin and morphine are opiates and opioids, but Percocet and Demerol qualify only as opioids.

The end results, though, are the same and can be tragic.

Marquette County Assistant Prosecuting Attorney Andy Griffen said the legal impact goes beyond charging people with drug-related crimes — many families in the county are grieving the loss of loved ones through these offenses.

And they’re not victimless crimes, he said. The victim is the person who’s doing the drugs.

Members of the panel audience raise their hands to show they’ve been impacted by substance abuse in one way or another. (Journal photo by Christie Bleck)

“Nobody chooses to get up in the morning — everything is going great — and they say, “I’m going to go become a drug addict. I want to go destroy my family. I want to go get in trouble in the law. I want to spend time in jail. I want to lose my job.'”

Unable to take control of their circumstances, their drug addiction leads to other crimes like home invasions, including elderly people with prescription drugs.

“They have this urge that’s so strong that they can’t control it, and as you get into these levels of crimes, the justice system typically calls for, and winds up, sending them off to prison,” Griffen said.

He had a few sobering statistics. During 2016, Marquette County felony charges that were related to drugs only — not the ancillary crimes like home invasion — totaled 117. There also were 216 misdemeanors.

The goal of Drug Court, a felony-level circuit court program, is to get people’s addiction under control, he said.

Dr. John Lehtinen of UP Health System-Marquette, a certified addictive specialist, called addiction a “brain disease” that’s separate from a lack of willpower or judgment. Instead, it’s a neurotransmitter-mediated matter.

“They have no control over the disease,” Lehtinen said of addicts.

And that addiction doesn’t go away.

“Once you have the disease of addiction, you have it for the rest of your life,” Lehtinen said.

However, he pointed out that people’s drug use initially is almost voluntary, but addiction compels the person to continue to use the drugs.

Genetics and an environmental are factors, he said, but the top risk factor for drug addiction is early use by school kids and teenagers.

Lehtinen showed drawings of what’s going on in the brain of someone who’s abusing drugs versus someone who’s not. What could be particularly concerning to many is that even if someone stops taking drugs, it takes a year for areas of the brain to heal.

“Most people relapse within three to six months,” Lehtinen said.

Another troubling fact is that many people become addicted to painkillers through legitimate uses, such as taking them for a broken leg.

“You’re going to see more and more physicians refuse to prescribe opiates and narcotics for justifiable reasons right now,” Lehtinen said.

The problem is that they manage pain but are mood-altering.

So how does a community combat this epidemic?

It’s not that easy.

Spending time in jail might not enter a drug user’s mind, or if it did, it still wouldn’t matter.

“If death is not a deterrent, then arrests are not either,” Lehtinen said.

Medication-assisted treatment has to be a part of the solution, he stressed.

“Most treatment programs offer minimal physician involvement and there’s a lack of addiction-medicine physicians,” Lehtinen said. “If I’m the only one in the Upper Peninsula doing this, that’s a problem.”

One popular medication used to treat drug issue is Naloxone, which Lehtinen explained is a short-acting rescue medication for opioid overdose.

Community partnerships that include families and law enforcement can help fight the addiction issue, but Lehtinen mentioned another problem: insurance.

“Eliminate prior approvals, prior authorization and standardize criteria for coverage,” Lehtinen said. “It is unbelievable the hoops I have to jump through to try to justify people getting medications they need to be on, have them continue to stay on and have them approved for treatment.”

Alicia Thatcher, a pharmacist at Campus Pharmacy in Marquette, addressed the addiction problem from her end.

“Addicts are not ‘those people,'” Thatcher said. “They’re your neighbors. They’re your family members. You can’t tell by looking.”

She’s also had to fire two employees for stealing prescriptions drugs from her pharmacy, despite them knowing they were on camera.

Thatcher pointed out that medications used to treat addicts can be “incredibly helpful” when used in the right setting and with the right support. However, they’re not a cure-all.

“There has to be counseling,” Thatcher said. “There has to be the desire to get well.”

On a personal level, she suggested people dispose of unused pain medications so they don’t fall into the wrong hands — such as young people — and if they do keep them, lock them up.

“Get them where they’re not going to be accessible,” Thatcher said.

Marquette County Sheriff Greg Zyburt called for understanding, people he had arrested earlier in his career contacted him during his campaign for sheriff.

Those were people who said he treated them with dignity and respect and who now are married and have jobs.

“If we’re getting someone, and it’s the lowest point in their life and they’re working the way up, God bless them,” Zyburt said.

Several other “Cost of Addiction” forums are scheduled, with Wednesday’s event the first of a five-part series.

Christie Bleck can be reached at 906-228-2500, ext. 250. Her email address is cbleck@miningjournal.net.