Ken Burns is completely wrong about the Iroquois

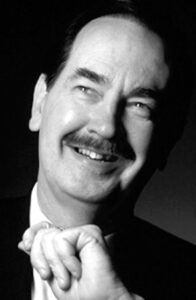

Rich Lowry, syndicated columnist

Few documentary films have the natural authority of a Ken Burns production.

The narrator of his works, Peter Coyote, is as close as we have today to “the voice of God,” the phrase once associated with legendary CBS anchor Walter Cronkite at the height of broadcast news.

This makes it especially outrageous that Burns feeds the viewers of his new epic documentary, “The American Revolution,” a childish canard at the outset.

Burns implies that the Iroquois Confederacy, a union of six Indian tribes in New York State, crucially influenced the founding of the United States. This is a nice fairy tale, but has no connection to reality, and Burns and his colleagues — who worked on their project for a decade — had time to verify the claim.

At the beginning of the film, the narrator intones that “long before 13 British colonies made themselves into the United States,” the Iroquois had “a union of their own that they called the Haudenosaunee — a democracy that had flourished for centuries.”

We are told that Benjamin Franklin “proposed that the British colonies form a similar union,” the so-called Albany Plan. He printed a famous cartoon of a chopped-up snake illustrating his point with the legend, “Join or Die.” The narrator continues, “Twenty years later, ‘Join or Die’ would be a rallying cry in the most consequential revolution in history.”

There’s much to unpack in this passage, which is carefully constructed to be misleading without being flagrantly false (although it doesn’t quite succeed).

It is true that the Iroquois forged an enduring confederacy, but this was hardly a unique contribution to political practice. History is littered with other examples. Greek city-states forged a confederacy against Persia in 478 B.C.

The film suggests a connection between a statement made by Iroquois leader Canassatego recommending a union, on the one hand, and Franklin, on the other, but this is will-o’-the-wisp stuff.

Canassatego shared his opinion at a 1744 conference over the Treaty of Lancaster, a negotiation between the Iroquois and several colonies. For his part, Franklin cited the Iroquois having a confederacy in one sentence in a 1751 letter about the possibility of a colonial union. That’s it.

It’s not true that the 1754 Albany meeting, by the way, was the prelude to the world-historical events 20 years later. The conference was not formed in opposition to Britain. Rather, it was a function of British colonial policy, which sought to keep the Iroquois from allying with France in what would become the Seven Years’ War.

The idea was that by uniting the colonies it’d be possible to better regulate, and smooth over, colonial relations with the Iroquois.

Regardless, the Iroquois had no role in our constitutional history. As the scholar Robert Natelson has noted, the Iroquois don’t show up as a model in the 34-volume “Journals of the Continental Congress,” the three-volume collection “The Records of the Federal Convention” (in other words, the Constitutional Convention), or the more than 40-volume “Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution.”

As for the Iroquois confederation being a democracy, it’s laughable agitprop. There were no elections; leaders were selected by women elders, whose status was hereditary.

In an interview with the TV program “Amanpour & Company,” Burns said that the contribution of the Iroquois led him to believe he had “to center” the story of Native Americans. Surely, it’s the opposite — he wanted to center the Native Americans, so he played up the Iroquois story.

It’s bad history one way or the other. “The American Revolution” has been praised by The New York Times for seeking to strip away what Burns calls “the barnacles of sentimentality and nostalgia” around the event. Actually, the film creates new barnacles more congenial to an audience that wants romanticized history about oppressed groups, but not about our own story.

So it goes in elite opinion two hundred and fifty years after the greatest event in the modern era.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Rich Lowry is on X @RichLowry.